December 7, 2022 -- Researchers from University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering have developed a method to find proteins located in close proximity to each other inside a cell. The technology, described December 1 in the journal Nature Methods, uses high-throughput genomic sequencing to measure proteins, protein complexes, and mRNA within individual cells.

Most methods to determine cell proteins involve grinding up a large group of cells, then characterizing their genetic material. But just as five individuals differ significantly from a family of five, these methods lack information about protein interactions. Single-cell mRNA sequencing shows the abundance and activity of certain proteins, but not whether they are forming complexes.

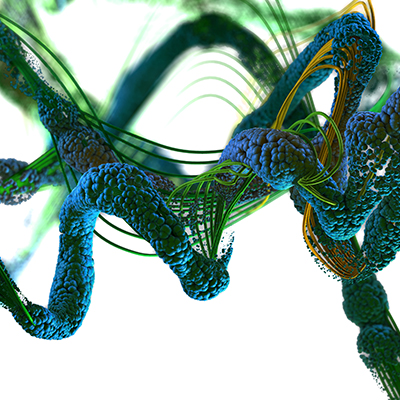

To discover proteins near one another, the researchers developed probes that attach to proteins of interest, with DNA tags extending outward. If two proteins are physically close, their DNA probes stick together like velcro. After examining hundreds of proteins, routine sequencing finds bound-together DNA probes, revealing paired proteins. Since the approach -- called Prox-seq -- uses standard sequencing, researchers can simultaneously analyze a cell's mRNA to find correlations between mRNA and protein abundance and function.

The team first tested Prox-seq on B cells and T cells, two human immune cell subsets. Prox-seq differentiated the cells based on their protein interactions, but also identified previously unknown cell subsets based on small differences in protein groups' organization. Using human-derived peripheral blood mononuclear cells, they simultaneously measured 38 proteins and 741 protein complexes on each cell and discovered a new protein complex that defines naïve T cells.

The researchers then used Prox-seq to study how proteins change their arrangements when immune cells called macrophages activate in response to a pathogen. They identified both known pairs of interacting proteins, as well as new protein groups that identify whether a macrophage has been activated, and even the pathogen that caused it. Having tested the method on cell surface proteins, the researchers are now working to expand it to additional proteins.

"I think this method is going to be a major resource for the molecular biology community," senior author Savas Tay, PhD, professor of molecular engineering at the University of Chicago, said in a statement.

Copyright © 2022 scienceboard.net